Clean Data Is the Foundation of Effective Machine Learning

Reproducing what I wrote for The New Stack where it first appeared.

Data science isn’t just for tech companies anymore; and it is slowly becoming a significant part of data teams, whether you are an enterprise looking for IT modernization or a startup trying to achieve the unicorn status. What used to be a bastion of data engineers, BI teams and data analysts talking SQL is increasingly being infiltrated by talks of linear regression and reinforcement learning. Machine learning and AI have solved some real-world business challenges for companies who are today reaping the rewards for making the right investment at the right time. Recommendation engines on Netflix, predictive analysis on Spotify, and multilingual speech-to-text systems by Google are among the most widely shared examples of this success.

With this in mind, CEOs and CFOs are reaching out to their CIOs and engineering heads with problem statements along the lines of

- Company X increased its revenue by 10% by doubling down on hidden market segments which were brought to light by Machine Learning. Can we apply AI to our product line and achieve similar results?

- We are paying $20,000 per month to this cloud provider for storing data. Can we do some kind of AI or machine learning on this idle data and get a win for the board and boost PR?

Data science teams get formed with largely this context in mind. They are given a business use case and a problem statement and are expected to deliver stellar results, increase revenues, and decrease costs for the company

But the hard reality is that data engineers and scientists often spend weeks, and in some cases months, trying to clean, organize, and make sense of the data that’s been handed over to them by the customer’s Business Intelligence team.

The reasons for underperforming data science teams are manifold. However, well-researched studies and thought pieces say that dirty data impacts machine learning results but also has important implications on the performance of dirty data as well as the performance of data science teams. (Read this for six factors why data science teams fail.)

In short, before applying any algorithm or technique to the dataset, it is paramount to have quality and consistency in the dataset.

Anyone who has attended a computer science or programming class is familiar with GIGO or Garbage In Garbage Out. The same principle applies to machine learning.

Data science may be “the sexiest job of the 21st Century” (based on a study conducted by Harvard), but let’s dig deeper and understand what data scientists actually do on a day-to-day basis. A recent study by Forbes concluded that data scientists spend 60% of their time just cleaning and organizing the data. Now that gives a whole new perspective to this promising career of Data Science.

Typical Machine Learning Flow

Now that we have established that the majority of time on the job is consumed by data cleaning, let’s take a look at where it fits in the overall machine learning flow.

On a high level, ML happens in the following more or less sequential steps (let’s leave the feedback loops aside):

- Source Discovery

- Data Preparation & Segregation

- Feature extraction

- Modeling

- Model Training & Tuning

- Prediction

- Model Deployment

The focus of this article will primarily be data preparation and segregation.

Characteristics of Bad Datasets

I have come to an understanding that the Anna Karenina principle is universal and applies to this case as well: “All good datasets are alike; each bad dataset is bad in its own way.”

The implication of this is that no matter the dataset or use case, there will always be a data cleaning step. No amount of automation or edge case analysis will take it away (maybe a ML model trained on highly unclean and dirty data will one day solve this problem).

Some of the commonly seen data which makes a dataset “unclean” are showcased below. The reasons for these errors are usually due to human error at some point in the data lifecycle, however, some can be machine-generated as well.

Inconsistent Schema

Imagine you are in the data team of a football association that has requested all football clubs in the country to send detailed information of the players in the team. The guideline for clubs is to send personal details in a csv file (there was no time to build a web interface or an API). Now some of the clubs created the column headers in the file just as expected (name, age, place_of_birth etc). However, some of the clubs named it differently, missed a column or added some new columns (a column for firstname and a column for last_name). You as part of the football association will, therefore, be spending additional time on reconciling the data into a common schema.

Extraneous Text

This is when a value for the column contains unnecessary information. An example:

- date_of_birth column with “01/12/2018szuyl” instead of “01/12/2018”

This happens more often than you think and is a pain when it brings down the data pipeline or an entire day’s worth of data is not included in a query because 01/12/2018szuyl means nothing.

Missing Data

This is fairly simple to debug as it is just values that are missing. Scientists clean this by adding default values or calculating a value based on certain assumptions. Implications of missing data can be large in downstream ML models. If unchecked, it could lead to overfitting and an undertrained ML model.

Redundant Information

This is when the same data exists more than once in a dataset (think duplicated rows in a csv/xls dataset or duplicate key:value documents). Datasets with redundant data may lead to overfitting down the line. Duplicated rows are rare in a relational database these days since having primary keys being NOT NULL and UNIQUE is expounded in most computer science curriculums.

However, not all information is redundant, it depends on the context. If there is a IoT temperature sensor streaming two temperature records every five seconds then it is likely that there will be groups of data with the same temperature value. This may not represent duplicate data when calculating anomalies in temperature values in a time period.

Contextual Errors

These are some of the toughest to correct because it often requires “business” knowledge or contextual know-how of the dataset itself. Some examples:

- Consider a dataset of daytime temperatures in the most populated cities in the world. A temperature value 320 is impossible to be in Celsius or Fahrenheit

- Age is -46.3 years

- Earth’s axial tilt is 22 degrees. Is this even within the range of acceptable axial tilts?

Scientists often assume that the sanity check on data is “not my job”

Sorry to disappoint.

Garbage Values

Imagine a record in the first_name column is_ ’Ă._ This obviously requires cleaning up or UTF-8/Unicode conversion of some sort (unless it’s an Elon Musk thing). This is often the first pass which a data engineer needs to perform on the dataset. Unchecked, it could lead to some pretty hairy bugs in a downstream extract, transform and load (ETL) pipeline or feature engineering script.

Data Cleaning in Action

The effort required to clean data scales with the breadth and depth of the dataset. I’d like to walk you through a scenario from a while back where I iterated through multiple rounds of data cleaning efforts while training a simple ML model.

The objective was to build an automatic speech recognition system that can recognize spoken digits from 0 to 9.

We chose Kaldi to build the solution. There were three steps involved in achieving the perfect model:

- Collect dataset and create training and test sets

- Train the model on training dataset

- Test the model accuracy based on the predictions from test dataset

Now that seems simple enough, doesn’t it?

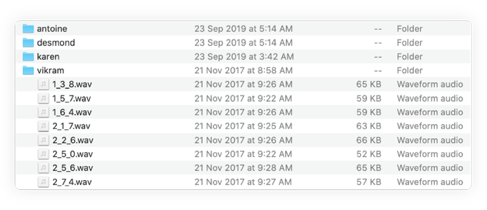

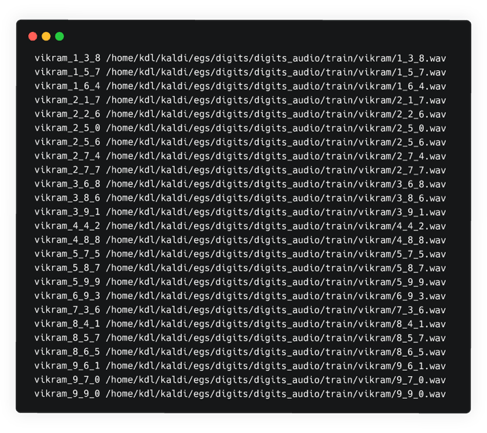

We had identified over a thousand speakers who were required to send us the data to be trained upon. The requirements for each speaker were: 25 WAV files of audio from each speaker sampled at 16000Hz. Each audio file is to be named after the digits spoken in that audio, for example if you say “1 2 3”, the file should be named “1_2_3.wav”. This naming convention is enforced by Kaldi and will be considered as a valid input to the Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) toolkit.

Each speaker optionally creates a textfile with the digits they have spoken:

Again, this may seem like a walk in the park. But it isn’t. Here are some of things which had to be fixed before the real ML work began:

- Wrong Filename

- 1_23.wav or 123.wav instead of_ 1_2_3.wav_

Our solution: We wrote a Python script to go over each file, validate the filename and make the change if required (string.split, string.replace was used)

- Wrong codec or container. This came under 2 cases

- The extension says .WAV but the encoding is MP3

- The extension says .MP3 but the encoding is WAV

- Our solution:This was a bit tough to solve, we used ffmpeg to validate that we are using the right codec here. If it was the codec, we used a shell script to reencode it.

- Wrong sample rate

- We expect each audio file to be recorded in 16k Hz (simple to do with Audacity). However, about 30-40% of the recordings we received were recorded in 44k Hz.

Our solution: We used ffmpeg and a script to downsample the audio to 16k Hz

List of fixes for the text file

We made a mistake of having this as an optional file. We shouldn’t have made this a requirement. Instead, the right way to do this is to generate this file from the names of the audio files. We made this an option for the participants so they would be rigorous in the process of recording their audio. What you say is what you document.

However, at that point in time, we received the textfile from half the participants. For the second half which sent in their files, there were challenges with formatting which needed to be addressed, for example

- Missing delimiter or duplicated delimiter \r\n: we received files with_ 123789_ in one line instead of _123\r\n789._

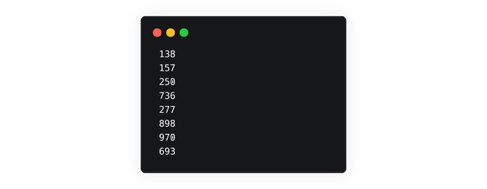

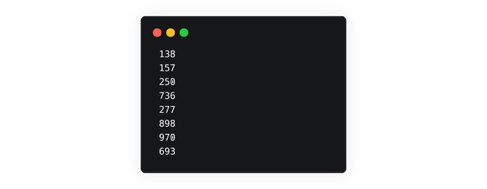

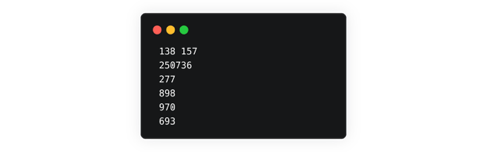

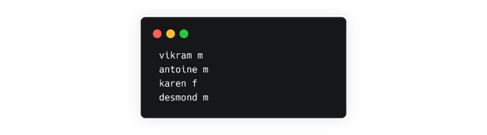

What you expect:

What you get:

We abandoned the approach of fixing the textfiles sent in by the user as there were too many edge cases to handle. A decision was made to auto-generate the text file after fixing in the file naming issues with the audio files.

Data Preparation

After cleaning the dataset, we had to do another additional step of data preparation to make the dataset ready for machine learning. This step was not as painful as cleaning the dataset but it was still another hurdle to jump before the machine learning could begin.

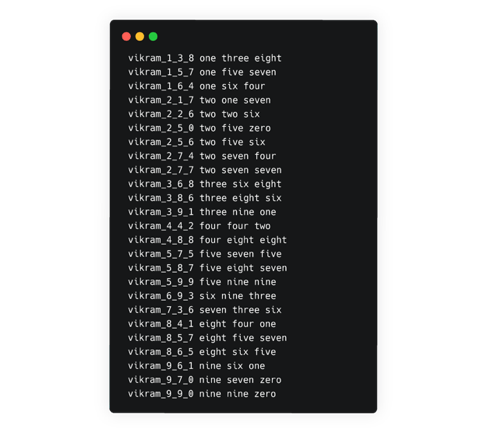

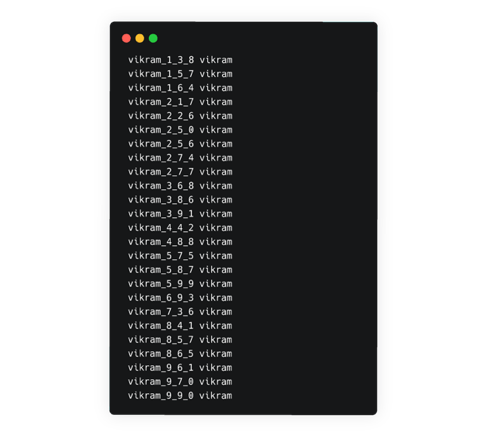

Why is data preparation required? Simply put, Kaldi expects the input to the ASR ML program in a certain format. With the cleaned dataset in hand, we had to create the following text files:

- 1 spk2gender file

- 1 text file

- 1 utt2spk file

- 1 wav.scp file

These files can all be generated using the information provided by the audio files and the textfile. We spent a day writing the Python script to generate these files.

Once this was done, we spent all of two days running the ML algorithm customizations, model tuning, and deploying it to the cloud.

Here’s a shoutout to some of the tools used:

Key Tenets to Keep in Mind

What are the final takeaways? This is the section that sums the post up with “tips and tricks” and “ninja tactics.” In short, you can put these points as TLDR or in a slide deck for management.

Data Quality Plan

Start by creating KPIs for your dataset. Set guidelines for the quality of data in the system. This ensures that all data enters your system only after following a predefined set of rules. This process starts with profiling current data sources and points of entry and ends with defining the workflow of data in the system including any new data sources in the future.

Data Standardization

This is a qualitative step that begins by asking the question “Is the right data entering my systems?” If unimportant data or incorrect data is entering your system without being sanitized, then it leads to additional effort down the road when time may be a critical factor in getting insights.

It is important to store raw data. There may be future use cases or legal/compliance needs which depend on it. However, it is prudent to have that stored in archival. For more day to day data needs, a layer of prepared data should be readily available in datastores.

Data Validation

Verifying the accuracy of data is paramount to the success of the data team in delivering a business outcome. On a high level, this involves verifying the source of data and verifying the accuracy of a data point. If you are getting weekly dumps from a third-party provider, you need to assess whether that data is reliable, how they collect the data, what steps they take to clean it and how they manage access to it.

Having custom rules depending on the dataset to verify if the data points make sense is critical. If a value in the age column is negative, it’s more than likely that it is incorrect. If the justification is “No negative value in the age column represents the delta between the estimated year of death and today, then maybe that column should not be called age.”

Data Hygiene

This involves end to end hygiene of the datasets to include fixing of:

- Inconsistent schema

- Extraneous text

- Missing data

- Redundant information

- Contextual errors

- Garbage values

Yes, but those scripts can be reused/automated to a high degree.

Although you have to manually write code to clean up every dataset since it is a unique schema, there is always room for automation.

Enrich Data

Purists will argue that this is part of the ETL step or it “depends on xyz..” but it is valuable to do a first pass at enriching the data by appending or aggregating fields to create a cleaner schema. Getting a column in Fahrenheit and non-US members are tearing their hair out? Just add a column for Celsius. Append last name to the first name and have a single name column. The use case depends on how you plan to consume the data.

Automation

All the points made above require thought, planning, and coding. It is important to automate these processes into systems as and when a pattern emerges. Think of it as a CI/CD pipeline for your data. All the automation gets integrated, gets tested and the ‘build’ is nothing but a dataset meeting its KPIs for quality and consistency.

Closing Thoughts

At the end of the day, the tasks which bring maximum visible value to the business is the machine learning piece. That’s the reason teams go through the trouble of spending so much developer time with data cleaning and preparation.

However, there is a point to be made about the value of bringing rigor to the data science process by having a system or process around data cleaning and preparation. Once these systems are designed and automated, there is a path for the data to go from unclean to clean. Always remember that automating something once is far better than doing something manually way too many times. The process of getting there will be arduous and painful, but it will bear sweet fruits for everyone.

Photo by Jeremy Perkins on Unsplash.

comments powered by Disqus